Thimble Rigging Extraordinary.

A Ghost Story and its Denouement.

Not very long ago the locality of Great Wheal Alfred was a very fitting one for a Ghost Story. Its untenanted, ruinous engine houses, through which the wind passed moaningly, and its sterile heaps of rubbish, gave it a weird aspect. But now the scene has changed. Busy machinery and busier mortals, brought there by mining enterprise, have made the place more civilised and human, and it is one of the last spots one would look to for a ghost.

An old man and woman named Oliver inhabit one of the few houses there, with a daughter; and some weeks since it got rumoured that an evil spirit troubled them. Spite of philosophy or religion a belief in the supernatural still prevails, and the neighbourhood was soor alarmed. Nightly the house was visited and noises which could not be accounted for assailed the ears of the horror-stricken ghost-seekers. These mostly took place in the dark and when the old couple had retired to rest.

Now it proceeded from the floor, now from the ceiling, and anon from in and around the bed. Clergymen, dissenting ministers, ‘praying men’ – all waited on the couple – but to ‘bell, book, and candle’ as well as to simple earnest prayer the ghost was alike inexorable, and resolutely continued its tenancy and its noise.

One evening the room was full of people. The lights had been put out and all were waiting for the ghostly sounds, when a loud crash came, a rush was made across the apartment, the consternation was fearful, and when lights were brought the old woman was found removed from one bed to the other. She solemnly asserted that a spirit had forcibly conveyed her from one bed to the other, and the marks and bruises on her person attested to some extent the story. The alarm now increased, and a ghost that – not content with frightening people, laid violent hands on them was viewed with horror.

At length, we are informed, the Rev. Mr Seccombe, of Hayle, and a Mr Hooper, of Copperhouse, visited the house. Now the latter was up to a ‘move or two’ in table turning, spirit rapping, etc., and was rather sceptical in the matter of ghosts. He and Mr Seccombe were determined to investigate thoroughly for themselves. After questioning the old couple Mr Hooper proposed to watch, and to fire with a pistol at the spot from which the noise proceeded. The old woman begged him not to, for it would only increase the spite of the ghost! This made him suspicious.

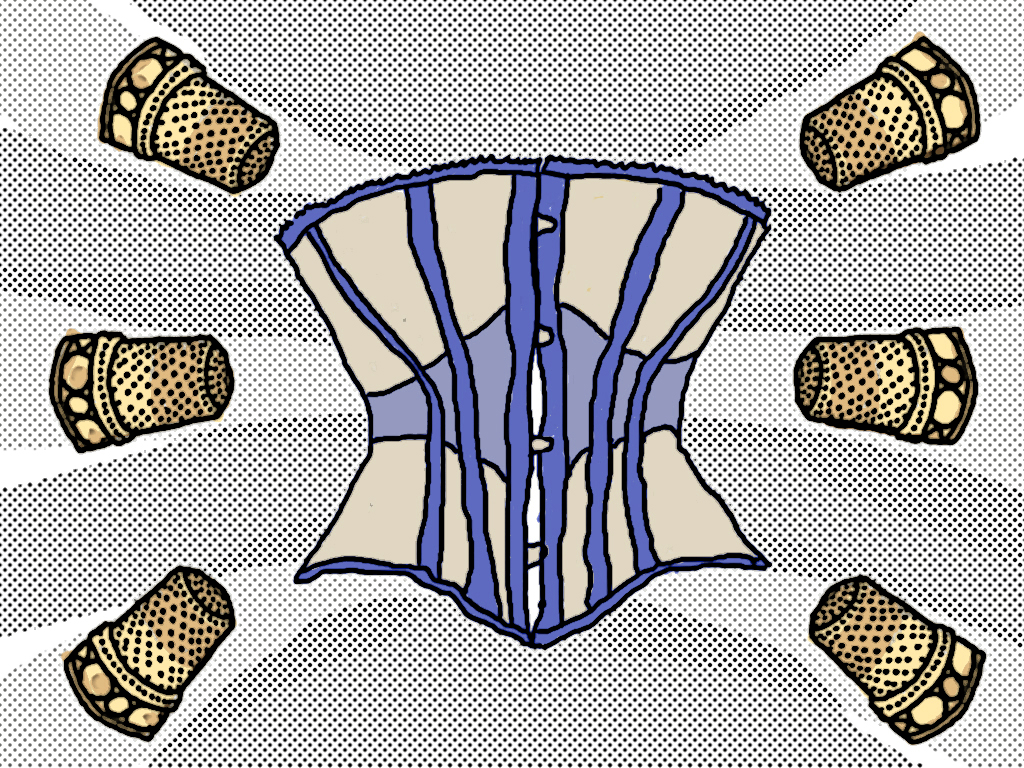

He suggested that if a ghost had any brains, a heavy stroke with a bludgeon might bring him to his senses. The old woman begged that harsh measures should not be resorted to. They watched for the sounds, and when those sounds fell on the ears of sceptics they had a far different effect than on the ears of believers – the words ‘sceptics’ and ‘believers’ being taken in a ghostly sense – such an effect in fact that the evil spirit was detected in a thimble which the old woman had on her finger and with which she rapped on the ‘bone’ of her stays, or on each side of the bed. The crowds had been most thoroughly thimble-rigged! and the imposition was detected and exposed.

The Cornish Telegraph, 5th November 1856.

Cornish Antiquities and Folk Lore.

Wheal Alfred. – A Cornish Ghost Story.

The Cornish of the present day – like their near relatives, the Welsh, and their more distant kinsfolk, the Irish and the Scotch – are, from the very force of their common descent, a people of somewhat sensitive temperament, and given to much enthusiasm, as existing circumstances may influence and immediate causes lead them. A keen apprehension of the invisible is generally ever present with them, and, acting upon the safe principle “That it is better to believe too much than too little” in matters of Christian faith and practice, they, not unfrequently indulge in and mix up with the graver questions of the same, the element of superstition, which is but the weak and sometimes erratic handmaid of a practical and true system of religion. That the Cornish ever have been a distinctively religious people may be read in their history from the earlier dawn of Christianity amongst them, and down through its middle ages, as well as seen and experienced at the present time. […]

And so endeavouring to bring the very spirit of this Christmas-tide to bear upon any passing tale of “folk-lore” relating to the seen or the unseen – trifling in itself, and only interesting as one of popular tradition – a rural superstition – we kindly invite any of our readers, so disposed, to accompany us to Wheal Alfred, and, according to an earnest request made to a clergyman of our acquaintance, then residing in that neighbourhood in the year 1856, to leave his house somewhere about 10 p.m., one calm Sunday evening in the summer of that year, and go with him up to a cottage near that mine, to “Put a dead thing out of the house” (as the messengers expressed it) “which had for some seven days sorely troubled them and their neighbours in the adjoining house.”

In the year 1856, and amidst the “workings” of Wheal Alfred Mine, there stood – and may now be most probably standing – a block of buildings, consisting of two ordinary miners’ cottages, facing a bye road, where all around the surface soil of earth appeared to have been turned inside out. Dwarfed and rugged mounds of grey killas, tinged here and there with colours of brick-dust, red, and dark olive-green, according to the nature of the minerals below, forming “collars” to gaping mine shafts, which almost seemed to yawn out a dull and deadly fascination for lookers-down to take a “jump in the dark” – go down, beating from side to side, till memory failed, and all sensation had gone. And then, running behind, and up along to these lone cottages, were cold-looking, arid ridges of the same “mine-stuff,” bearing a few scattered stems of furze, with stunted plants of the ox-eyed daisy and dandelion, struggling with the cold and acrid soil for very life.

And above this desolation loomed out the “drums” of many a disused “horse whim,” with long coffin-shaped wooden structures, for conveying water to various works on the mine, with the fractured and bulging walls of one or two “fire whim” buildings, engine and counting-houses, all deprived of doors, window frames, and with roofs half stripped by the winds; and with floors all sodden and neglected within, in each instance suggestive of death and decay, following upon scenes of active and busy life. And as the night-wind swept on and beyond each ridge-top and hollow trench below, they who lived there might well think that, at times they heard “tokens” – calls to them from beings of another world, impelled by some unknown power thus to revisit earth, and so, moving hither and thither, as the memories of their past lives might lead them, amid the old familiar places of earth, and by the “portent” of a blue and gliding flame, or the “token” of a deep though stifled moan, coming upwards with the chill breaths of air, from the gloom of the mine-shaft beneath; or, again, in the more household “warnings” of the cry of “night-birds,” the “ticking of the Death-watch;” “the coming of the ravens to the window,” etc., bidding them thus communicate with the departed for weal or for coming woe.

It was, then, in the year 1856 that the two cottages in question were occupied severally by the families of two miners, still living there, as they might, though the mine in its integrity had then ceased to work – the one facing the road, by a miner, his wife, two sons, and three daughters; the other, under the same roof, but more turned away from the road, by a younger miner and his newly married wife. It is to the former of these that the tale, now to be told, refers.

We suppose any one of our readers to be, on a certain calm Sunday evening, in the summer of 1856, with the clergyman in question, the hour, say 9.30 p.m., and the household preparing for the night. Somewhat urgent applications for admittance are heard suddenly at the entrance door, adn upon the parties being taken into another room, and the clergyman asked to see them, he enters the same, and a good and fearless-looking young mine-captain, half supporting a woman agitated and hysterical, stands before him; and after a few broken expressions of terror on the part of the woman, by way of apology and explanation, the mine-captain says: – “I am sorry to disturb you, sir, at such a late hour, and on a Sunday, too; but I offered to come down from near Wheal Alfred, where this person and her family live, just by way of company, for she is too much frightened to come by herself, and the others remain to guard the house, and to ask you if you would be so good as to go back with us and look into the matter, as they will not else be satisfied, for they say they have had no rest for the last seven days, by day or by night. Noises like those of a person clicking his finger-nails together, groaning, grinding his teeth, with occasional heavy blows at the head of the father’s bed, coming and going, sometimes by day, but continually by night, when the candle is put out, and they wish you to come and put the dead thing out of the house.”

Argument and remonstrance being all in vain – though the mine captain admitted the truth and reason of both – the clergyman kindly consents to go. “Because,” said the captain, “They have had three pious men there all the evening trying to put the thing out, but it is too strong for them.” On our way up by Angarrack Viaduct – the poor woman of the “haunted” household groaning, the captain encouraging, and ourselves speculating as to what we may see, hear, or be expected to do – and after crossing many a lonely field and lane in the course of a some two-mile walk, we come upon a sort of crazy, dilapidated shed by the wayside, a very picture of misery, desertion, and want – windowless and doorless, its thatched roof half gone, and its floor encumbered with heaps of refuse from the mines, and from accumulated ruin within – when the woman grasps the miner’s arm, and utters a suppressed shriek. “Do not be afraid, sir,” says he; “a poor brother of this person hanged himself, unfortunately, in that shed about a year ago. Maybe it is but fancy, sir; but something like a shiver in the air, or as a large bird flying past, did seem to go by me just now, for that poor young man worked with me at Wheal Alfred for many years. Did you feel anything, sir?”

We are now approaching the two cottages in question, and from the “hunted” (haunted) one, and through the open door, come sounds of deep voices groaning, and, apparently praying, ejaculating, and expostulating, and addressing something within hearing, but not in sight. We enter, and standing round a table with a book (seemingly a Bible) upon it, are three elderly, grave, and quiet-looking men, evidently miners, with a sort of pained and saddened expression of countenance, not uncommon among men of their dangerous calling, and these are the friends sent for “to put out the dead thing, but it was too strong for them.” From the only room above, used as a bedroom for the whole household – father and mother, two sons and three daughters, and all grown-up men and women – there come down the sounds as of people wailing and praying, broken by a sudden scream on the part of one of the daughters, which seemed to run into, and culminate in spasmodic shouts – “Glory! glory!” “Mercy! mercy!” “I will be saved!” &c. We are invited to go up into this room, and in it we see three beds, the roof is open to the thatch, and upon these beds are sitting the father and mother, two brothers, and two sisters, and lying all along upon the floor a third and elder sister, beating the same with her hands, rolling her head from side to side, and shouting – or, rather, screaming – out the words and others similar, as just mentioned – “My daughter, Sir, has been taken down under prayer this evening, at a revival in —- Chapel, and we are so glad and grateful to you, sir, for coming here this evening. We cannot rest – we have not slept for nearly seven nights, except for a few minutes in the daytime, because there is a dead thing in the room. It begins clicking when the light is put out, and when I called upon it to answer by knocks if it were the spirit of —-, a heavy blow came just behind me, there, as I was lying in the bed.”

All were requested by the clergyman to leave the house, except the father, mother, and two sons, and we hear him as being with him speak something to the following effect: – “You all here believe in Jesus Christ; that He, as God, is All in all now – is not only all-powerful but all mercy and all love. Now even supposing that He, as God, had determined to allow any of such communication being made to you, not in accordance with his usual manner in these later days of the Christian religion, would His doing so in such a manner as you are led now to think, be consistent with His divine character? The sad Bible story of the rich man’s prayer from the unseen world – ‘I pray, therefore, father (Abraham), that thou wouldest send him (Lazarus) to my father’s house – for I have five brethren – that he may testify unto them,’ &c. – certainly shows the possibility of a return – a warning from the spirit world – but, if not granted then, why, on the general principle of the case – should it be allowed now? God is all powerful, so no angel could come to earth – no spirit of the departed return from the spirit-world without His permission. God is also all mercy and all love, and so, even if such an extraordinary permission were given, or means of communication allowed, in your case would it be carried out, in the way you now describe? so frivolous and vain – calculated only to frighten and alarm? Would not the message come in a way consistent with what you read and believe of your Saviour while on earth, and, as now, all-powerful, but all-loving and merciful in Heaven?”

“We believe all that you say, sir; but there are these noises, and we have no rest from them, and by knocks it says that it is the spirit of —- from Australia.” “Put out the light,” says the clergyman, “place me behind the bed, between it and the wall, from whence the sounds proceed, and at that part where the blows come.” “The spirit will tear us, sir,” the man replies. “For all that, do as I say,” the clergyman repeats. It is done; but beyond that of beating heart from within, and the voices of a wailing crowd without, nothing is seen, no sound is heard. Again, and after almost ten minutes’ suspense, the clergyman reasons and speaks as before, leaves the cottage, escorted home by the mine captain with a request that he might be informed as to how matters went with the troubled household on the following day.

One more visit – say on the folllowing Wednesday – may just suffice to have the report of the family in question, to hear what is said by their many visitors (for it is said that the cottage was beset nightly, and for upwards of a fortnight, by a curious and excited multitude), as well as to have the opinion of the clergyman, and, in suggesting a moral, to offer our own.

We enter the haunted cottage in the afternoon of the succeeding Wednesday; the family are all there, and with the exception of the mother (as the clergyman remarks), still evidently terror-stricken and truly scared. “After you left, sir, on Sunday night (says the father) we had rest till the middle of Monday, when the thing came back, and was more savage and noisy than ever. It went under the beds making a sort of sweeping sound upon the floor; then up to the rafters where it made a noise like a cock crowing; it grinded its teeth; and this very day, sir, no sooner did you come near the house, than it made a lot of raps on the wall and was off again, and when you leave the place it will come back again as bad as ever.”

And a similar report, in words much to the same effect, was made at some three or four following visits to the scene of action; tho’ after running in a course of local wonder and mystery (for the cottage and its occupants had become rather notorious as little centres of a marvellous tale), for some twenty-one days or more quiet and order gave promise of a gradual return, and all the sooner perhaps on account of a watchful scrutiny and strong representation on the part of our acquaintance the clergyman made to the wife of the tenant of the cottage itself. However, the lookers on, at our first Sunday visit, said that “As the clergyman entered the bedroom in question, and as he was heard by them as speaking to the people in it, a blue flame came out by the window and was seen to go on towards Hayle and the sea,” &c., &c.

The tenant of the cottage subsequently, and as an earnest of his belief as well as appreciation of the clergyman’s support, offered willingly to “pay him £5 as a fee, and by instalments.” The clergyman thought that though detecting no symptoms of real fear in the “tenant’s” wife, he yet apprehended a disposition on her part so to give the block of buildings a “bad name” (in working upon the credulous and excited temperaments of other members of her own family as well as that of her newly-married neighbour), as to get possession of both cottages, additional space for her own household being much needed, and her neighbour’s part of the block having a small garden but her’s none; and as a moral it may be advanced that covetous people have indifferent consciences and only fear transactions with mortals or others, when it appears that they may get the worst of the bargain. As for our own opinion, in this ghost story, we agree with our friend the clergyman. As for the tale itself, its only interest lies in the fact that it did occur at the time, place, and in the same terms as here repeated. — W.J.M.

Royal Cornwall Gazette, 26th December 1879.

Two Ghost Stories: One in Cornwall, the other Elsewhere.

For Narration on Christmas-Eve.

The Ghost of Great Wheal Alfred.

(By Now-And-Then.)

I know scores of boys, as boys they were, and about my own age, then living in Gwinear, Phillack, and St. Erth, who can vouch for a period in knocks, rappings, scratchings, and slaps. To the extreme eastern boundary of Great Wheal Alfred, in the parish of Phillack, and, on a bit of wastrel that touches the mine-track as it goes into Laity-hills, there stood two cob-built houses. In the southernmost lived a large family of father and mother and grown-up sons and daughters, and a child, the illigitimate offspring of one of the daughters. The disturbance, from beginning at nightfall, at the first, gradually widened itself into the day; until, at last, it became a common occurrence for any one, and at any time, to successfully call for a ghostly knocking, just for the asking, and the giving of alms!

The most serious part of the affair, as far as I know, were the slaps that flew about so roundly, and on members of the family indiscriminately, save the mother and her love-child. Herein lies a grave suggestion, which, for want of a higher testimony on the matter, had better be left on the recognised tablets of society, as already existing.

The “Ghost of Great Wheal Alfred” at last became so obstreperous that it raised the whole neighbourhood, when prayer-meetings, revivals, and every other incentive to good works were advertised and projected. But still, the obdurate spirit held on and made things lively to a degree.

At last, the parsons of the locality held consultation how to lay the disembodied visitant; and at it they went. How many it took I know not now, or the exact functions each, or all, possessed in ecclesiastical procedure. But bell, book, and candle, revivals, prayer-meetings, with other formularies peculiar to ghost-laying were of no avail in this case. The knocking, and the rest, continued until nothing more was left to knock upon. And, not until the family had notice to quit, and doors and windows and roof had been lifted, and nothing was left but the bare stumps of the foundation, did the devil pack up and go too.

Cornishman, 24th December 1896.