An American Ghost Story.

The Cock-lane ghost has made its appearance at Amherst, Nova Scotia, to the excessive wonderment of the inhabitants, who could scarcely be expected to recognise their visitor offhand, and detect the staleness of its playful tricks. In Cock-lane the ghost was more than suspected of collusion with a servant-girl, and with a servant-girl it seems to be on terms of intimacy now.

At any rate, peace and quietness reigned, undisturbed by supernatural phenomena, in the dining-saloon of Mr John W White until Miss Esther Cox entered that establishment as a “help.” With her came the ghost, whose first exercise was to open the oven door and shut it again with a bang, in obvious contravention of all rules for good baking. Mr White naturally resented this, and endeavoured to coerce the refractory piece of iron by means of an extra fastening; but lo! the door flew off its hinges, and fell with a clatter at the feet of Miss Cox.

In the midst of the consternation thus caused, a gentleman described as “hitherto one of the most incredulous of Amherstians,” appeared, and, with Mr and Mrs White, formed a committee of investigation. The door was replaced, refastened, and closely watched; but the watchers failed utterly to discover the means whereby, for the second time, it broke loose.

Then rappings were heard on the floor, and questions answered. “Who are you anyway – the devil?” queried bold Mr Rogers, and three loud raps gave what was taken as an affirmative reply. “Are you after Miss Cox?” Again three raps answered. “Yes;” upon which the ‘incredulous’ Amherstian waxed bolder, and said, “You want me, too?” This time only one rap followed, and was understood to mean that the company of Mr Rogers was not required, at all events, just then.

Of course the fame of these mysterious doings soon spread, and we must say for the Ghost that it did not disappoint expectations. Mr White’s furniture began to move about in an alarming manner. Boxes and buckets shot across the floor untouched by human hands, and a chest of tea actually followed Miss Cox out of the shop, and might have gone further had it not got jammed.

Next the young lady’s pillows took to gambolling round her head instead of softly sustaining it, and two hats placed on the bed as she lay “rolled up in the quilts” performed a lively dance in presence of nine witnesses. At last the Ghost took to writing most improper things on the walls, doing so invariably in the dark, and when Miss Cox was by.

On one of these occasions a gentleman of an enquiring mind suddenly struck a match and exhibited Miss Cox acting as substitute for the disembodied scribe, whose stock of bad language had, perhaps, run out.

Since then Amherstian incredulity has largely increased, but the latest scientific phase of the matter shows up Miss Cox as an involuntary agent of the spirit which haunts her. Mr White, her master, supports this view, and declares his solemn belief that the girl is “chockfull of electricity.”

Huddersfield Chronicle, 11th January 1879.

Spiritual phenomena in Nova Scotia.

From time to time particulars have been sent to us from Nova Scotia about spiritual disturbances in a house there, differing in no way from the generality of such phenomena. But of late they would seem to have grown stronger, as set forth in the following summary from last Tuesday’s Evening Standard:-

“Few people in the present day remember anything about the Deil of Badarroch, although his doings were at one time the cause of no little talk. His operations were carried on at a farmhouse in the North of Scotland, and took the form of making crockery jump off the shelves, peats fly out of the stack at the unsuspecting passer by, and various other articles perform strange and unaccountable evolutions. Ministers were called in, and prayed long and loud with a view of exorcising the evil spirit which every one believed to be responsible for this unnatural state of affairs; but prayers availed nothing with the author of the mideeds, and even the ministers became targets for peats and other missiles. Wise men were called in to explain the phenomena, but their cause remains unexplained to the present day.

A similar state of things to that which was witnessed at Badarroch is exciting a whole country-side in Nova Scotia. In this case, a girl, Esther Cox by name, is the object of the evil spirit’s attentions – taking it for granted that the general belief on the subject may be accepted – and of course she has been interviewed. The reporter states that while Esther was standing washing dishes a glass tumbler came down with a crash, and shortly afterwards the rim bounced up and went flying over her head. Esther, it is said, could not have caused these acts, and no one else was in the room.

Other articles pitched themselves or were pitched at her from a distance of fifteen feet or so, and struck her .A bath brick and a scale of weights then commenced to misbehave themselves, and finally the crockery and furniture generally commenced to move about in a frantic manner, and to forget, apparently, their ordinary functions, or at any rate to object to perform them. The most serious part of the business, however, was the conduct of what is described as a vicious jack-knife, which, inspired with a sudden hatred of Esther, who had, perhaps, rubbed it the wrong way in cleaning it, twice attacked her and stabbed her in the back, drawing blood. Surely never was jack-knife before guilty of such atrocious behaviour, and the acts became none the less unaccountable when it is considered that before making these cowardly and unprovoked attacks it had to open itself.

The household gods generally, if we are to credit the newspaper reports of the affair, have been converted into household devils, and all this to annoy poor Esther Cox. When such deeds are done – when furniture is suddenly endued with life and motion, and a jack-knife develops vicious propensities, for which, unfortunately, the law as at present constituted proides no adequate punishement, the feats of Spiritualism become tame in comparison.”

Spiritualist, 13th June 1879.

A Haunted Girl in Nova Scotia.

Attempted Assassination by Invisible Agents.

At Amherst, in Nova Scotia, there is a good deal of excitement in regard to the alleged persecution of a young woman by spirits, who hurl missiles at her, and who have, on more than one occasion, apparently attempted her assassination. A gentleman of high literary position in London, who knows something of the circumstances, and who is not a Spiritualist, has kindly furnished us with the following extracts from the Amherst Gazette, from which it will be seen that the Editor of that Journal personally testifies to some of the mysterious occurrences.

Esther Cox, who is the object of these so-called spirit persecutions, is employed at White’s Saloon in Amherst; and the Editor says –

The case has lately, on account of the undoubted nature of the testimony to several remarkable incidents having occurred, in which it was impossible for Miss Cox to have been the voluntary agent, excited increased interest. Persons who previously would give no credence whatever to reports in the case have been satisfied of its bona fide character by personal observation. Among those who have recently received new light on this subject, we observe that the Sentinel, which some time ago thought there was entirely too much made of the matter, refers to the actual hurling of various objects about Miss Cox by four spirits.

Having often been asked if we had ourselves personally observed any of the strange occurrences, we will say that until Tuesday we could speak from personal knowledge of the rapping only, the reality of which we had already tested by causing Esther to place herself upon a stool which would not admit of her feet touching the floor.

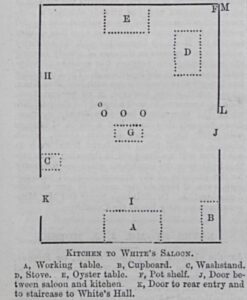

To illustrate as plainly as possible the developments and reported occurrences of the past week, we give a diagram of the room in which matters have been particularly lively this week. This room is attached to the rear of White’s Saloon. Esther was standing at I, washing dishes. Our position was a little outside of the door J. She had not moved from her position when we heard a crash, and, on going forward, found a glass tumbler, which had evidently contained a paper of pepper, had been broken in pieces by falling upon a large earthen bowl which lay upon the table. Esther said the tumbler came from the top of the cupboard, B, and the spot struck and position of the pieces were sufficient evidence that it had at least come from that direction. The distance was 7 feet. A rim of the top of the tumbler was unbroken. Taking the same position we saw, a minute or two afterward, this rim flying over her head, and it fell at H and was shattered. She was still at I washing her dishes, and could not have thrown it herself, nor was any other person in the room.

This is all we have seen. We have frequently heard drop articles which she said struck her, and which we were told by reliable persons had been hurled from certain points 6 to 15 feet distant.

W.F. Cutten, Esq., was standing at the lower side of door J, and Esther on the upper side, L, when a pile of scale weights he had previously seen on the counter, 12 feet distant, fell near their feet.

While Mr R. Hutchinson was standing at L he heard a hard substance strike the ceiling of kitchen and afterwards the wall of saloon at M. Picking it up he found it to be nearly a whole Bath brick, which Mr White and Esther said had come from a shelf between D and E.

On Tuesday evening, Esther, as she states, locked the shop to go to tea, and while crossing the street was startled by a tremendous noise in the building. She dared not return alone, and after meeting Mr Hutchinson they entered and found, as they both informed us, that the following articles had moved from various points to positions near the middle of the floor. OOO represent three earthenware bowls, 16, 14, and 12 inches in diameter, which had been on table A, inverted, and were now top upwards. In one was a tea-kettle from the top of stove, which with contents would weigh 20 lbs. In another a coffee-pot was found which had been on shelf at right of E. The box C was on its side at G. A basin which had been on it was at O, still containing water. A pot had come from F, and ranged itself near the kettle, so that one might not call the other names.

But of all the attacks upon the poor girl the most serious was that which she affirms was made by the blade of an open jack-knife, penetrating her clothing and cutting her back. Mrs White examined her back, and states that the mysterious assassin drew blood. Esther states that this was the second attack by the knife, which she and Mr White’s son say was closed after its first flight, and must have opened of its own accord.

Mr Cutten saw a basin of water, which he had previously noticed on a stand in this kitchen, move to a point 9 feet distant, and upset upon the floor. Esther had passed the stand, and the basin followed her at a distance of a few feet.

Esther was sitting in the kitchen at Mr White’s when a large glass bottle moved from a pantry shelf and was hurled across the kitchen floor, breaking in pieces, and was seen to do so by members of the family.

Mrs White placed some nails upon Esther’s lap, and in a few minutes they became quite hot. She told Esther to walk out, hoping there might be a cessation of hostilities. She went into the woodshed, when lumps of coal flew about and at her, and as she returned to the kitchen Mrs White saw a stone as large as her clenched hands follow her in, though she is sure no one was there to throw it.

The Amherst Gazette reports a large number of other incidents of a similar character, but the above will suffice to show the nature of “Esther’s persecutions,” most of which seem to have been fairly well attested.

Spiritual Notes, July 1879.

At the Sign of the Ship.

Last month I mentioned the comic Canadian case of diabolical possession. I have since written to the Amherst Gazette for information as to the contemporary reports in that ‘organ,’ but have received no answer. Here, at all events, is a resume of the tale for Christmas Eve.

Has America an unappreciated De Foe, and is his name Mr Walter Hubbell? The problem is raised by a little book devoid of covers and all bestained with the spilth of an ink-bottle. The work is named The Great Amherst Mystery (Brentanos, New York, 1888). It was sent to me by a schoolmaster in Canada, who took it from a bad boy who was reading it in school. My whole sympathy is respectfully offered to that boy, for I have rarely laughed more than over The Great Amherst Mystery. If it is ‘bogus,’ as some say, then De Foe was not so well inspired when he wrote about Mrs Veal. There is a simplicity, a directness, a quaint Yankee worldly wisdom, a prodigality of queer domestic details in this record of ‘the supernatural,’ which only a genius like De Foe’s could confer – that is, if the story is bogus. And if it is not – but no person of scientific training will admit that alternative.

Mr Hubbell, before publishing his book, was ‘duly sworn’ to the truth of his narrative before A. Ackerman, Notary Public No. 5, New York County, on February 13, 1888. But his oath is less persuasive than his guileless and unsophisticated character. He was acting in a strolling company during January-July 1879, and he visited Nova Scotia. He describes Halifax and St. John’s as if nobody had ever discovered them before, and suggests that the United States had better annex this eligible region. At Halifax he heard of a haunted house in Amherst, Nova Scotia, and, as he had exposed many spiritualistic impostors, he yearned to ruin the character of the Amherst mystery.

Amherst is a village of 3,000 people on the Bay of Fundy. The chief industry is shoemaking. The foreman in the factory was Mr Daniel Teed, who inhabited a comfortable two-storied cottage, and this cottage was haunted. With Mr Teed lived Mrs Teed, their son Willie, aged five, and George, a baby. Here also lived Mrs Teed’s sisters – Jennie Cox, a village beauty, and Esther Cox, who also had ‘handsome teeth’ and ‘an indescribable air of rugged honesty,’ but was possessed of a devil, or several devils. A brother of Mr Teed’s and a brother of Mrs Teed’s completed the family. They usually dined on ‘beefsteak and onions, bread, and delicious butter.’ The reader who remembers what the old farmer said to the Duchess of Buccleuch will not forget the cabbage. Esther was partial to acids, and would drink a whole cup of vinegar. she had also suffered lately from a very severe shock to the nerves. For further particulars see the Amherst Gazette, August 28, 1878, to August 1, 1879. This periodical, were it attainable, I would gladly consult, as Mr Hubbell recommends, for, says he, ‘I am fully aware that thousands of persons will not believe a word I have written.’

The trouble begins in 1878 – date not given. Elsewhere it is given as September 4, which does not correspond with reference to the Amherst Gazette of August 28. Esther and her sister Jennie had just gone to bed when Esther jumped out, exclaiming that ‘there was a mouse under the bedclothes.’ The wench in Cock Lane also felt ‘it’ ‘like a mouse on her back.’ Jennie decided that the mouse was in the straw of the mattress, and the maidens went back to bed. Next night something rustled under the bed. They got up to fight the mouse, and saw ‘a pasteboard box, which was under the bed, spring up into the air about a foot and then fall to the floor and turn over on its side.’ This performance was repeated, the girls screamed, but nobody believed their story.

Next night Esther jumped up, saying that she was dying and ‘about to burst into pieces.’ Her amazed family saw her ‘swelling visibly before their wery eyes.’ ‘I have asked a number of physicians if they had ever met with similar conditions in a patient, and all replied that they had not, and added, never should.’ Then ‘a loud report was heard in the room, followed by three reports, and the whole room shook.’ ‘Esther immediately assumed her natural appearance and sank into a state of calm repose.’ Next day ‘her appetite was not so good as usual. All she could eat was a small piece of bread and butter and a large green pickle, washed down with a cup of black tea.’ This is not a dejeuner which one could have recommended.

The attacks returned, and ‘all the bedclothes flew off and settled down in a confused heap in a far corner of the room. They could see them passing through the air by the light of the kerosene lamp… and then Jennie fainted. And was it not enough to have frightened any woman and made her faint?’ It was, indeed.

Dr Carritte was now called in. He is dead, which is a pity. He saw Esther’s pillow fly out of the bed and resist the efforts of a ‘strong, healthy young farmer’ to pull it. Then came a sound of scratching on the wall, where were found in characters a foot high the appalling words – Esther Cox, you are mine to kill!‘ ‘Every person could see the writing plainly, yet but a moment before nothing was to be seen but the plain kalsomined wall.’ ‘Pounding noises’ began and things flew about. The ghost, like Glam, ‘rode the roof’ and was audible in the street. Now the facts got into the Amherst Gazette. A bucket of cold water, ‘to all appearances boiled,’ as at Stockwell in 1772, but effervescent powder will account for that. ‘The most exclusive class’ (O democracy!) began to call at the cottage. ‘The ghost’ now told Esther that he would set the house on fire, and he often did, as at Rerrick in 1691. ‘The inhabitants had various theories. Dr N. Tupper suggested a good flogging,’ which, I incline to think, would have proved efficient. Esther was now boarded out, and nothing occurred, as in the case of William Morse (1681). In about a month the game recommenced, and Mr White, with whom Esther boarded, was annoyed. A box weighing fifty pounds floated in the air, and the editor of the Amherst Gazette witnessed some of these peculiarities. At a Mr Van Amburgh’s, nephew of the lion-tamer, Esther enjoyed a period of peace.

Now Mr Hubbell comes on the scene. In Newfoundland he read the reports and thought that there was money in it. Why not run Esther at a lecture on ‘the greatest wonder of the nineteenth century: a simple-hearted village maiden followed by a ghost from Nova Scotia’? On June 11, 1879, Mr Hubbell arrived at Amherst and determined ‘to run the enterprise as a business transaction.’ He would ‘expose’ the ghostly part. He saw a few miracles, wrote his lecture on June 12, and started on tour. Esther ‘had to carry a large fan on the stage, so that she could hide her face in case she should commence to giggle from hysteria,’ as was not at all improbable.

Singular to say, after about four lectures, ‘Mr White informed us that, if we continued our tour, we should all eventually be slaughtered.’ The public took to throwing ‘brickbats, drowned puppies, and dead rats,’ and so the tour ended on June 20. But Mr Hubbell stayed on at Amherst, where all the furniture kept flying about, appearing, disappearing, and so forth. A seance was held, Rock of Ages was sung, ‘but it disgusted the ghosts,’ who ‘never did much on Sunday,’ perhaps for fear of spoiling Esther’s Sunday raiment. The ghost set the house on fire, and ‘until I had had that experience I never fully realised what an awful calamity it was to have an invisible monster somewhere within the atmosphere, going from place to place about the house, gathering up old newspapers, and, after rolling it up into a bundle and hiding it in the basket of soiled linen or in a closet, then go and steal matches out of the matchbox in the kitchen, or somebody’s pocket, as he did out of mine, and after kindling a fire in the bundle, tell Esther that he had started a fire, but would not tell where, or perhaps not tell her at all… I say it was the most truly awful calamity that could possibly befall any family, infidel or Christian, that could be conceived in the mind of man or ghost.’

Now, if Mr Hubbell wrote these natural and breathless sentences by dint of pure literary cleverness to counterfeit the agitation of an artless and sincere chronicler of events, I venture to say that America has found and neglected her De Foe. Once Mr Hubbell said it was odd that the ghosts spared the cat. ‘She was instantly lifted from the floor to a height of five feet into the air and then dropped on Esther’s back, whence she rolled to the floor.’ One of the ghosts made Esther blush by taking her (Esther’s) stockings and putting them on. ‘I commanded Maggie, who, of course, was not visible to me, to take them off instantly, adding that it was an infamous thing to do… In about a minute a pair of black-and-white-striped stockings fell out of the air…’ ‘One of the demons cut a triangular gash in her forehead with an old beefsteak bone’ (relic of happier days!) ‘from the yard.’ Could De Foe beat that old beefsteak bone?

The end of it was that Esther got four months for wilful fire-raising in a barn; ‘I was not there to explain.’ But her virtuous life and unlucky situation ‘raised a whirlwind of popular sentiment in her favour,’ so she was let out in a month. She married, before 1882, had a little boy, and as far as is known, no more trouble. Her nervous shock, from a revolver in the hand of an undisciplined admirer, is dated August 28, 1878, a week before the first mouse, if that is rightly dated on September 4. The earliest newspaper quoted is after Mr Hubbell went to Amherst, but takes for granted that the disturbances are familiar. The Amherst Gazette also published Mr Hubbell’s journal, kept after his return from his brief and unsatisfactory tour in the provinces.

Omitting a vast deal of similar matter, there is the gist of Mr Hubbell’s story. On his own theory of ‘astral bodies’ he is probably an incarnation of the author of The Ghost of Mrs Veal. What we need is a file of The Amherst Gazette, so to ascertain what basis, if any, Mr Hubbell had for his entertaining little volume. He assures his readers that, since his experiences, he acts the Ghost, in Hamlet, in a new and realistic way. It is a small but exacting part, and, though said to have been taken by Shakespeare himself, does not indicate that Mr Hubbell has risen very high in his interesting profession. What he can do in literature is plain to the critical student.

[the chapter then turns to other topics]

A. LANG.

Longman’s Magazine, January 1895.

At the Sign of the Ship.

[…]

Just as the last Ship was launched, I received from Nova Scotia some information about Esther Cox, the heroine of the Great Amherst Mystery, of the green pickle, of the convulsions, the raps, and the volatile objects. First, there is The Central Ray, a college magazine published by the undergraduates of the Central University of Iowa (May 1893). To this a gentleman named Morgan contributes a letter on the Amherst Mystery. He, like myself, had read the ‘Great Amherst Mystery,’ and made inquiries. He received (April 24, 1893) a reply from Mr Arthur Davison, Amherst, clerk of the County Court there, and this is published in The Central Ray. Mr Davison is ‘no believer in spiritualism,’ but has a theory that there is a ‘magnetic power’ inherent in human beings, and that in Esther Cox’s case this ‘became unhinged.’ Esther was for three months a maid in his employment, ‘and a better we never had in twenty years.’ ‘I have often watched her to see how she came downstairs; she seemed to fly.’ This is precisely what many respectable witnesses said in the case of Miss Shaw, of Bargarran (1697), who was thought to be bewitched, and who founded the thread manufactories of Renfrewshire. A Mrs Margaret lang was burned, with several others, as the guilty causes of the phenomena!

The author of the Great Amherst Mystery ‘painted the facts up, to make the book sell, but the facts were there all the same’. ‘She was very much afraid of this Thing,’ as she called it, and when Mr Davison tried to make her direct the force by conscious willing, ‘she became afraid’ and desisted. Mr Davison describes a scene (as does Mr Hubbell) in which he and her physician, Dr Carrette (now dead), saw her lying very ill, her body suddenly swelling and collapsing. While she lay thus a rapping began on the footboard of the bed, grew loud, louder, and then she opened her eyes and recovered consciousness. ‘It was the hardest scene I ever witnessed.’

When Mr Davison was sitting between Esther and an open drawer full of knives and forks, a fork arose, flew at him, and hit him on the head. ‘When a man gets a whack on the head, it then, with him at least, assumes a reality.’ On another occasion, Mr Davison, entering his stable, saw Esther going out, followed by a currycomb. He stepped out of the path of the infuriated currycomb, which hit the doorpost. He picked it up, and does not say that he observed any attachment to string, horsehair, or the like.

Another time he met Esther at the door of the stable. She had the milk-bucket in one hand, in the other she was just taking a key from Mr Davison (whose left hand held a bundle), when a two-quart pail of water came off the table inside, and spilt itself over Esther and her employer, ‘spoiling my cuffs.’ The table, within the door, was round a corner, at a distance of six or eight feet, as shown in a diagram. Many other objects flew about; finally, Esther (as we saw last month) was put in prison for setting the barn on fire.

That is the gist of Mr Davison’s evidence. A gentleman of position at Amherst has examined witnesses, and totally disbelieves in the ‘ghosts’ and the ‘intelligent rapping’ as ‘admitted imposture’. The phenomena described by Mr Davison remain ‘inexplicable on ordinarily received theories.’ ‘It is possible, though not probable, that she managed it by means of horsehair, or other almost invisible strings.’ This, of course, could not be the explanation in the case of the water-dipper.

A physician, who attended Esther when confined, after her marriage, ‘never saw anything supernatural about her in any way – quite the contrary.’ Only ‘some ignorant or weak-minded people were believers.’

Mr Davison cannot be called ‘a believer’, but he was certainly an intelligent and perplexed observer. So there we leave Miss Cox to the judgment of the ages, merely remarking that her malady or imposture is identical with dozens of historical instances, in which hysterical persons, to put it at the lowest, exercised an art of trickery that it would be hard for Mr Maskelyne to rival.

In the Devonshire case, given by Miss Florence O’Neil, the heroine, or victim, was a girl of the best possible character and the trouble (as in Esther’s case) began after a sudden fright. but we never hear of any such matter among the innumerable fantastic, tricksy, hysterical patients studied by the great French specialists in nervous diseases. These patients are certainly capable of any imposture, and it is odd that they never try to repeat the effects (so well known in popular tradition) of ‘the Demon of Spraiton’, and of Esther Cox.

ANDREW LANG.

Longman’s Magazine, February 1895.

A Critical Study of “The Great Amherst Mystery.”

By Dr. Walter F. Prince.

It is forty years since “Bob Nickle,” “Maggie Fisher” and sundry other ghosts were supposed to “cut up” in the Teed cottage in Amherst, Nova Scotia, rapping and banging, tipping over chairs and tables, dropping matches from the “atmosphere” and setting fires, shying paper-weights and table knives at the heads of the unwary, and sending all sorts of easily portable objects through the air, not to float down and settle softly as in many another narrative, but rudely to smash and bounce just as though you or I had thrown them.

Mr Walter Hubbell, the actor, who spent about a month in the Teed homestead prying upon the demons which supposedly clustered about Esther Cox, began in 1879 to tell the story to the world, and continued to do so in enlarging editions, until the tenth in 1916, by which time the total output, quite comfortable for himself and his publishers, of fifty-five thousand had been reached. William James approached the case with respectful interrogation, Andrew Lang was undecided whether to wonder or to grin at it, and Mr Hereward Carrington has admitted it among his “True Ghost Stories.”

Nobody, however, has hitherto seemed to find time to look into the “Great Amherst Mystery” with a critical eye, and rather stiffly to demand of the ghosts what real evidence they have left on record in behalf of themselves. It is time that this were done. (Notes 1 and 2.) It is worth doing, for the case has become in its way a classic, and has produced one sort of impression or another upon some hundreds of thousands of people. The first question to ask, in essaying this pleasant task, is:

Who are the Witnesses?

One of the first things which strikes the attention is that the witnesses are so few. The spectators, indeed, we cannot doubt were many. Not only Hubbell (3), but Dr Carritte, a local physician (4), and Davison (5), declared that “hundreds” of persons witnessed the phenomena. The numbers of persons visiting the cottage could hardly have been hallucinatory, though the amount of phenomena witnessed by the most of them, and the conditions, are another question. But one wonders exceedingly, when he reads of the wealth of testimony said to be available, that so few witnesses are actually heard from.

Mr Hubbell did not get a statement from a single person to insert in his first edition, though he alleges that his story was “fully corroborated by the inhabitants of Amherst and strangers from distant towns and cities, whom I saw and talked with.” (6). Even newspaper items, dubious as they are for evidential purposes, had a discouraging tendency to emanate from one source – Mr Hubbell. He indeed speaks of there having been a number of accounts in the Amherst Gazette which were copied into other papers, the year before he arrived on the scene (7), but he quotes from none, as he would probably have done had they been serviceable. But when, after Hubbell’s advent, the same Amherst Gazette has an article on the subject (8), it is based on Hubbell’s statements.

Afterward that paper published an account two columns long, but composed of extracts from Hubbell’s journal (9). The “Western Chronicle” article, also inserted by the author of “The Great Amherst Mystery,” was based upon the same extracts, which it pronounces “remarkable, not to say tough statements.” (10). A “Banner of Light” article is also quoted, but that too, has Hubbell for its authority (11). The Moncton Dispatch article (12) was not inspired by Hubbell, but it contains no assertions which present difficulties, while the Moncton Times article is mostly from an editorial in the Halifax Presbyterian Witness, which attacks the genuineness of the phenomena and the propriety of exhibiting the girl for money (13). Mr Hubbell attributed the latter article to the machinations of an enemy, in the shape of a business rival, angry with the actor for having seen Esther, and the chance to acquire useful quarter-dollars, first.

These are all the press reports which he gives sign of, though he mentions an account in the Daily News of St John, and a much later one in the New York Commercial Advertiser (14), but these, too, by a singular (?) fatality, are made up of Hubbell’s own testimony.

The author of “The Great Amherst Mystery” was warned, before his edition saw the light, that ample testimony to the genuineness of the phenomena was needed. He himself prints the article which appeared in the Halifax Presbyterian Witness, and was compied in the Moncton Times of June 19, 1879, declaring: “The Amherst Mystery, we are informed on the best authority, is no mystery at all, except to persons who refrain from using their powers of observation and reason. The only mystery is that so many persons who should know better are deceived.” The fact that an indefinite percentage of the “hundreds” who visited the Teed cottage were unfavourably impressed is never hinted at by Mr Hubbell, but it is confirmed by the independent investigators of Andrew Lang, some years later.

Mr Lang says (15) “On making inquiries, I found that opinion was divided, some held that Esther was a mere impostor and fire-raiser.” And yet the first editions of the story were allowed to go forth with no direct testimony from a soul beside the author of the little book!

As time went on, it was forced upon Mr Hubbell’s consciousness, probably by criticism, that he should make some effort to obtain other testimony. In July, 1905, he wrote to Dr Richard Hodgson to see if the S.P.R. had additional evidence in its possession. The reply of Dr. Hodgson (16) emphasises the strangely elusive nature of those hundreds of witnesses. This states that Professor James sent a student to make inquiries in Amherst, but owing to time elapsed and probably lack of interest in the student, nothing of value was added. It might be that this report was sent to England and got entombed. “I believe, however, that I am right in saying that in any case such inquiries as were made later on did not contribute anything that would be of importance for you to add to any future edition of your book.” Significant fact! that an especial embassy to the scene of the wonders, coupled with the indefatigable capacity of the American Secretary of the S.P.R. for curious investigations, could extract nothing of importance from those hordes of witnesses! Dr Hodgson added the assurance that “If we can lay our hands upon any memoranda in connection with the case, I shall be glad to send them to you.” But evidently nothing was found and sent.

Still later, June 20, 1909, Prof. James wrote (17), saying “It has been a tremendous pity that no evidence extraneous to your account has ever been got on that extraordinary case.” But Mr Hubbell remarks upon this: “Prof. James never having read this new edit

Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research, Vol. XIII (1919).