Spooks at the Rectory.

Missiles flung from roof by unseen hands.

Spooks or mischievous boys – local opinion is divided – are causing discomfort at Ardrea Rectory (near Cookstown, co. Tyrone), once the home of the Rev. Charles Woolf, who wrote the famous poem “The Burial of Sir John Moore.” Showers of bricks, bottles and the like are keeping the present occupier, the Rev W.E.R. Scott, and his household in a state of some liveliness. Police and special constables now garrison the house, and have done some shooting, so far without winging a single spook. The scene of the attack is the rectory yard, to the right of a three-storeyed structure. The missiles are flung from the roof by unseen hands. No one cares to approach this part of the grounds, and strangers have been warned to keep clear of the premises. Cookstown police and a strong force of special constabulary are on duty at the rectory day and night, and the shots fired in order, if possible, to frighten off the intruders have been without effect.

Liverpool Echo, 22nd March 1924.

Ardtrea Rectory Ghost.

Considerable excitement has existed around Ardtrea during the week in consequence of the pranks of what was supposed to be a ghost in Ardtrea Rectory. Stones, etc., were flung about, a bottle of vinegar was broken at the front door, etc. The police were requisitioned when the inmates could not get to the bottom of the affair, and the P Specials were on duty, but as usual in all such cases it was discovered that a domestic servant was responsible for the “supernatural” occurrences. She confessed, and the ghost was laid.

Mid-Ulster Mail, 22nd March 1924.

The Ghost of Ardtrea.

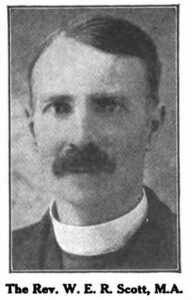

By The Revd. W.E.R. Scott. M.A. Rector of Ardtrea.

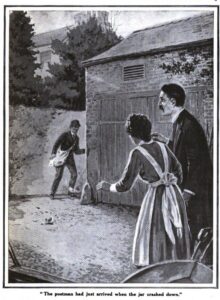

Illustrated by W.G. Whitaker.

An odd little story from Ireland, describing the strange events which happened recently at an old rectory with a somewhat sinister reputation.

In the parish of Ardtrea, in County Tyrone, Ireland, stands the big rectory in which I took up my abode, with my family, on my appointment to the living in 1914. It is a curious house, with a curious history – a huge, grim, rambling building standing in the midst of forty-five acres of grounds. Erected over a century ago for a wealthy incumbent, at a time when parochial values were very different from what they are to-day, the atmosphere of the place seems to be impregnated with that peculiar blend of mystery and superstition which surrounds so many old houses of the kind.

The rectory of Ardtrea, however, would appear to have more justification than most for the mixed feelings with which it is regarded by the simple countryfolk around. Its very situation lends itself to thoughts of the mysterious. Magnificent beech trees stand upon the lawn, and other forest giants and mournful yews are ringed about the grey old mansion. The long carriage-drive, too, is guarded by a noble avenue of great trees, and thick masses of ivy cluster upon the walls which flank the great wooden door enclosing the courtyard.

If its situation and appearance bear the impress of the unusual, so likewise do its traditions. One of its first inhabitants, Dr. Thomas Meredith, a former Fellow of Trinity College, Dublin, Rector of Ardtrea for six years, and the great-grandfather of my wife, died within its doors in 1819 from “a sudden and awful visitation,” as his tombstone states. Exactly what this was no one seems to know, but the story runs that a governess employed by Dr. Meredith was troubled by a ghost, which took the form of a lady arrayed in white – possibly, averred local tradition, the virgin Saint Trea, who lived hereabouts in the fifth century.

This apparition greatly troubled the good doctor, and on the advice of a friend he charged a gun with a silver bullet and lay in wait for the midnight visitor. In due course a report was heard, and next day the Rector lay dying upon the flagged floor of a basement room. From that hour the country-people looked askant upon the “haunted” house, and avoided it whenever possible.

Long ago, a curate named Neve was murdered in a rebellion, his skull being found many years afterwards in the bed of a rivulet. My predecessor, a most popular clergyman, over seventy years of age, met his death in a strange way. A workman quarrelled with another man, and the Rector’s rather delicate son intervened, with the result that the ruffian knocked him down. This so upset his father that he took to his bed and died in a few days from heart failure.

Such, then, was the house to which my acceptance of the living brought me in the autumn of 1914. My wife and I already knew something of its sinister reputation, but that troubled us not at all, since we promptly placed the stories in the category of “old wives’ tales.” Even so, there were times when one was inclined to wonder whether there was anything in the alleged malign influence of the place, for various illnesses assailed my family with more than customary venom. However, the doctor’s skill dealt efficiently with these, and it was not until nine years had passed that there began the extraordinary series of events which at first tempted me to believe the most extravagant of the stories which passed from mouth to mouth anent the house in which I lived.

To appreciate fully the narrative that follows, it is necessary to bear in mind the position of the rectory with its environment of trees and dense shrubberies, in which, even in daylight, not one, but many persons can remain concealed. they are such as probably surround few houses, and, together with the outhouses, form “cover” of an exceptional kind.

There were four of us at home at the time – my wife, my eldest daughter, myself, and the young general servant, who just then was our only domestic. On March 24th of this year the latter came in while we were quietly chatting and announced the first of the “manifestations” which, when they reached their culminating point, almost made me doubt the evidence of my own senses. “Someone,” she said, “has torn the tarred felting from the outer hen-house.” This was annoying, but I had to make the best of it, so I took out a hammer and nails, and tacked the material on again. Next day the maid told me that once more it had been ripped off. Again I mended it, and again I found it torn. Three times this happened, and finally I found the hen-roosts themselves interfered with. That night I waited up with a flashlight and a stick, but nothing happened, and after vainly searching each building I returned to bed.

The following day I found two strong stable door-posts torn up and lying outside the coach-house. I had them removed and placed inside the padlocked yard door, but, twenty-four hours later, one of them was missing. A large wooden partition in the stable had also been wrenched off and lay on the ground outside. Naturally I was furious at this wanton damage, as well as considerably mystified, but watch as I might, I could get no glimpse of the perpetrators, whose next “invisible” accomplishment was to fling down a leaden pipe and tap from the outer wall of the coach house. The maid suggested that this might have been used to assist someone to climb into that building, but when I searched once more I found no traces of anything of the sort.

That night a strange sound of crashing was heard, and I ran out into the yard in the moonlight to see large stones rolling down the outhouse roofs. Occasionally a jam-pot or tin rattled on the slates. “Now,” I thought, “I’ve got you, my lads!” I flashed my light into every bush and shelter, but all in vain. No one was discernible. By this time Susan, the maid, was with me, and though naturally she appeared alarmed at what was happening, she accompanied me down a narrow path, flanked by a high wall, which led to the garden. As we walked along it an occasional large stone, quite capable of cracking one’s skull, plumped over the ivy-clad wall and fell at our feet. But once again my search was fruitless, and though intermittent missiles were still appearing – apparently from nowhere – I gave it up and went back into the house.

All next day, from nine in the morning until eleven at night, the same thing occurred at intervals. My daughter climbed up the high wall at the pillared entrance to the yard and searched through the ivy massed upon it, while I did likewise with other walls, and even got up on to the roof of the rectory itself and searched the space between the chimney-stacks. The result was the same – there was no one to be found.

By this time the news of what was going on had spread, and that evening a few members of the special constabulary arrived at the rectory, armed with rifles. To tell the truth, I was glad to see them, for these inexplicable occurrences were most annoying. The constables persuaded me to stay indoors, saying that they intended to fire if they heard anything. Sure enough, a little later, eight shots rang out in rapid succession, and I dashed out on to the lawn to see what had happened. They told me they had heard some movement in the bushes and had promptly fired, but whatever was there when they did so, there was nothing tangible when they came to search for their quarry. They found the bushes as I always found them – empty.

For the remainder of the night three young “specials,” in mufti, patrolled the grounds, and next morning the Royal Ulster Constabulary sent out a sergeant and two constables on motor cycles, who took note of the missiles flung on roofs and doorsteps, and of the other damage done.

The grand offensive against the unseen disturbers of our peace, however, was reserved for the night following the firing. Twenty-five armed special constables arrived from all sides, surrounded the rectory, and kept watch closely. It seemed as if this demonstration in force was too much for our mysterious assailants; for the first time no stone or bottle was flung upon the lower roofs.

By this time the maid and I were alone in the house, my wife and daughter having left for a pre-arranged visit to the Free State, and I often wondered how the maid could remain, for the ghostly business was enough to shake anyone’s nerves. Added to this, the disused servants’ quarters consisting of large, gaunt, dungeon-like rooms, floored with large flagstones save for the tiled kitchen, and old wine vaults, cobwebbed and musty, are not very cheering for anyone in contact with them, while the occasional scurry of rats lends a horrid atmosphere to the long corridor. I must confess that I felt admiration for the girl’s pluck.

So far the solution of the mystery had completely baffled the Royal Ulster constabulary, the Special Constabulary, and ourselves. The granite steps in front of the house were littered with broken glass, and stones and empty tins lay everywhere. Nevertheless the police watch on the house was eventually withdrawn, as no objects were flung while the constables kept guard. It soon appeared, however, as if this step was premature, for the very next day Susan, the maid, and I were walking across the yard in broad daylight when we saw a large glass jam jar rise above the coach-house roof opposite to us and crash upon the cobble stones. I at once rushed for my bicycle, borrowed a gun and six cartridges from a parishioner, and, hastening back, fired three shots round the yard buildings to frighten the unseen thrower away. The postman had just arrived in the yard when the jar crashed down, and the shock was too much for his nerves. He departed somewhat hurriedly, and was afterwards heard to remark that he “wouldn’t live in that house for a thousand a year!”

But, although I didn’t know it then, the mystery was now not far from a solution. All at once Susan came running to me and told me that someone was hiding in the loft above the coach-house. from the end window of the top corridor of the rectory I saw that the far door of this loft was ajar, although I had driven staples through the chain to fasten it. Gun in hand, I crept on rubber-soled boots up the old mossy steps leading to the loft. “At last,” I said to myself, “I’m going to find something out.” I did, but it was not at all what I expected. To my utter amazement, I found two well-known women parishioners of mine in the loft, kneeling with their eyes glued to the openings in the venetian-shuttered window. “What on earth—” I began, and then they turned to me, with eyes alight with excitement, and told me what they had seen.

To say that I was dumbfounded at their story is only speaking the truth. More than that, I was almost incredulous – but I was shortly to have ample corroboration. Members of the Special Constabulary later came to me with evidence that could not have been more circumstantial. Susan, the plucky little maid, was the culprit – or at any rate the chief culprit!

I compelled her to confess, and gradually, little by little, the whole story came out. She had a friend, a young soldier – who was actually seen by the special constables leaving the grounds one evening, but gave a satisfactory explanation of his presence there – and the “manifestations” were a plot between them to drive us out of the house so that they could see more of each other than her duties as general servant allowed! In this they were aided and abetted by some of the soldier’s “pals”. The girl threw most of the missiles in the daytime, when no one was about, also dropping them from the upper windows of the rectory while we were at meals, or in the early morning before we were downstairs. At night the young soldier and his companions took up the fusillade until the number of constables on watch forced them to desist. Owing to the cover afforded by the shrubs and bushes, not one of them was actually caught in the act, but rumours reached the ears of the police, who already had their suspicions. The night they fired, the soldier and his confederates must have had a narrow escape.

In the case of the girl there was direct evidence, apart from her confession. My wife and I she deceived utterly – she had been with us some time, and we had always found her a good girl – but certain of my parishioners were not so credulous, and the two who were in the loft actually saw her throw crockery on the roofs of the outbuildings. When she found out that she had been observed she came to me, with almost incredible effrontery, and informed me that there were unauthorized persons on the premises!

There was, moreover, yet another witness of her guilt. The large jam jar which had fallen into the yard in daylight the day after the police were withdrawn was actually thrown by a special constable who wwas at work on my glebeland in the hope that he might encourage the girl to respond. The trick was successful. While I went for my gun the girl, believing her confederates were at work, stooped down, picked up something, and flung it on the roof. That evening the man came round in uniform and told me what he had seen.

The maid’s confession, of course, removed any doubt that might have remained. She was a wonderful actress to deceive us all as she did for a week or more. Naturally, I dismissed her summarily, and she has since written a letter to my wife, acknowledging her guilt once more and expressing contrition. The young soldier I tackled personally. At first he denied all knowledge of the affair, but on my threatening to acquaint his colonel of the matter, tacitly admitted the impeachment by saying that he “would turn over a new leaf, and would never take up with a woman again!”

So, with a very natural and prosaic explanation, ended an affair which at first certainly seemed to possess a touch of the extraordinary. There are still some of my parishioners, however, who remain firmly convinced that after a hundred and five years the “ghost” of Ardtrea has again been at its fell work, and it is no use trying to enlighten them.

The Wide World Magazine. An Illustrated Monthly of True Narrative – Adventure, Travel, Customs and Sport. Volume 54 1924-1925 November-April

In olden times belief in ghosts was almost universal, and no matter how sceptical people may be of such things nowadays, the ghost story still has a big appeal.

One of the most remarkable ghost stories of the present century, to my mind, concerns the happenings which took place a few years ago at Ardtrea Rectory, a huge, gaunt old building, near Cookstown, Co. Tyrone. An ancestor of the then rector’s wife had been in charge of the parish about a hundred years previously. It is said that this ancestor attempted to shoot a mysterious, white-clad figure which had been haunting the grounds for some time. Shortly afterwards he was found dead in the house, his gun beside him. A tablet – which can still be seen – erected to his memory in the parish church states, that he died from “a sudden and awful visitation,” and pays a warm tribute to his many fine qualities.

Well, it was said that the ghost had been “laid”, but would appear again in a hundred years. A hundred years came and went and then this affair started again. This time the ghost wasn’t visible, but bottles, tin cans, and stones were showered, apparently from nowhere in particular, and crashed down around the house. It was truly a nine-days’ wonder, for with more or less brief intervals, these astonishing conditions prevailed for that period.

Despite the efforts of the rector – the Rev. W.E. R. Scott, M.A. – and others, it seemed that the mystery could not be solved. Both in daylight and after dark the mysterious missiles thudded to the ground in various places about the house. The massive steps at the front of the rectory especially rapidly resembled a large rubbish heap. The R.U.C. and the Special Constabulary tried to solve the problem, and one night no less than 25 of the latter, armed with rifles, drove up the tree-bordered avenue to keep watch at the house. But nothing happened this time, and they went away no wiser.

Eventually the position was cleared up, largely owing to the rector. It was found that the maid was in league with a soldier home on leave, and with several others, all of whom lived outside the parish. At the time the trouble started the only persons at the rectory were the rector, his wife, one or two of their children, and the maid. The maid knew that in view of an approaching holiday there would be nobody in the house except the rector and herself. If she could get him away also, then she and the soldier – and perhaps some others – could have the house to themselves, she reasoned. If they were careful, they could make outsiders believe that the house was deserted, because it was haunted.

The idea may have been crude, but she admitted her guilt, and was, of course, dismissed. She had not been suspected earlier, as she had arranged with her confederates to carry on the bombardment while she was actually in the house, and the missiles were often flung when the rector’s wife could see the maid actually performing her ordinary household duties. The plotters were aided in avoiding detection by the “cover” formed by numerous trees, shrubs, and outbuildings around the house.

Her only confederate to have his identity discovered was the soldier, who was given twenty-four hours to leave the locality, if he did not wish the escapade to be reported to his colonel. He went, but before he did so exclaimed bitterly to the rector that he would “never take up with a woman again.”

Ballymena Observer, 25th December 1931.

The story of this ghost is an amusing one and should not be taken too seriously. In the parish church of Ardtrea, near Cookstown, there was – and I believe, there still is – a marble monument in memory of the Reverend Thomas Meredith, who was for six years rector. He died, according to the words of the inscription, “on the 2nd May, 1819, as the result of a sudden and awful visitation.” A local legend explains this “visitation” by stating that a ghost haunted the rectory, the visits of which had caused the family and servants to leave the house. Mr Meredith had tried to shoot the ghost, but had failed. Finally, someone advised him to try a silver bullet. He did so, and next morning was found dead at his hall-door, while a hideous being like a devil made horrible noises out of any window the servant approached. The man was advised by neighbours to get the priest, who would ‘lay’ the thing. The priest arrived and with him a jar of whisky, under the influence of which the ghost became quite civil, and remained so until there was only one glass of whisky left. The priest was just about to empty this out for himself, when the ghost made itself as tin and as long as a Lough Neagh eel and wriggled into the jar to get the last drop. Thereupon the priest hurriedly put the cork into place hammered it in, and, ,making the sign of the cross over it, had the evil thing secured. The jar was buried in the cellar of the rectory, and ancient villagers aver that on windy nights the ghost can still be heard calling to be let out.

Mid-Ulster Mail, 19th January 1929.

Another haunted rectory.

Yet another rectory is said to be haunted. This time it is England, but in some ways the case is strangely like to the ghost of Ardtrea Rectory, Co. Tyrone, which caused such a sensation a few years ago. I told you about the latter just before Christmas.

This ghost, like the Ardtrea one, includes throwing bottles in its activities, and one of these missiles nearly knocked a bit out of a reporter who arrived to investigate. That was most obliging, for the incident gave his story of the affair an extremely realistic effect.

But I am afraid I have lost my faith in ghosts. If the mystery of this English rectory is ever solved, I expect it will be found, as happened at Ardtrea, that the hands which threw the bottles, and carried out all the other ghostly deeds, were not supernatural but human.

Ballymena Observer, 22nd January 1932.