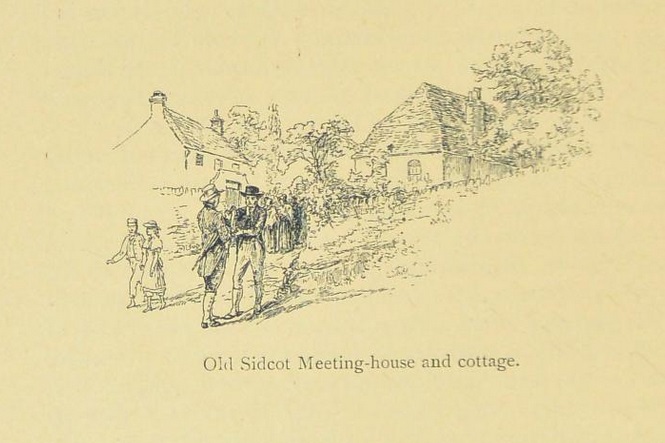

About a hundred years ago, there lived in a cottage, still standing, nearly opposite the old Friends’ meeting-house at Sidcot, a real Conjurer of the old school. His name was Beecham, and he had a wife whose name was Joan. He had the reputation of being a great “medicine man;” had a magic staff and books, wore a red cap, and was consulted as conjurer, or cow-doctor, whenever dryness in pump or cow, or loss of appetite in sow, disturbed the farmer’s peace of mind. The time came at last for the wizard’s staff to be broken, and his books to be wound-up. In view of the grave, he insisted on being buried under a certain tree in his own garden; telling his wife, if his directions were not complied with, “I’ll trouble ‘ee.” The mortal clay, however, when vacated by the conjurer, was decently buried in the churchyard; and the widow, diligent, not disconsolate, remained in the old cottage, earning her bread by making cakes and sweets for other people. Thus she lived till she died, no one ever finding her cakes bewitched, or her sweets turning supernaturally sour. She lived and died with the character of a plain, honest body – a good old soul.

But now for the marvellous part of the story. On the anniversary of the old conjurer’s death, or burial, tradition has forgotten which, one Wednesday morning, when the Friends were sitting in solemn silence in their usual week-day meeting for worship, their meditations were interrupted by the sudden appearance – not of Beecham’s ghost – but of the woman who lodged with his widow, and who took care of the meeting-house. Pale with fright, she cried, “Oh Friends, do’e come out; there’s all Joan Beecham’s things a vallen’ about the ‘vloor.” Two Friends, one a Minister, the other an Elder, solemnly rose and left the room, probably thinking more of preventing further disturbance of the meeting than of meddling with disturbance elsewhere. However, they followed the doorkeeper to widow Beecham’s, and there witnessed a kind of disturbance they had never seen or heard of before.

As they entered, a heavy, old-fashioned chair came to meet them; pots and pans were flung violently about; old Joan’s heavy pastry pan rocked up and down as if moved by invisible hands. The Friends were shrewd experienced men, with a full share of the sobriety and worldly wisdom, if not spiritual discernment, with which their Society has always been credited. They were not likely to be taken in by the trickery of two old women; but they could discover no imposition; nor could they ever explain or account for what they had witnessed.

The facts are undeniable. The report of the occurrence spread in the neighbourhood, and many persons visited the spot to inquire into the circumstances. Amongst others came Hannah More, but neither her superior sense and learning, nor the sagacity of commoner people could unravel the mystery.

The conjurer never troubled the widow again, and the occurrence gradually subsided into the general collection of ghost-stories. And so it might have remained, had not later experience caused some re-action from the general contempt for alleged supernatural occurrences. Cases very similar to that at Beecham’s cottage are said to be not unfrequently witnessed in “table-turning” circles; and though such reports are sneered at by those who have not witnessed them, their sneers are in turn smiled at by those who have. Sneers, however, prove nothing one way or the other. The facts are attested by too many respectable witnesses to be disposed of in that way. They are admitted by many scientific men, and various theories have been stated to explain them.

These theories, however, are little more than a classification and nomenclature of the phenomena. Mesmerism, which was decried as imposture fifty years ago, is now, under the more scientific name of hypnotism, deemed worthy of some examination. We now hear of animal magnetis, psychic force, unconscious cerebration, levitation, and so on; but how the psychic force and unconscious cerebration of the widow Beecham could have caused the levitation of her kneading-troubh, and her late husband’s heavy armchair, remains as much a mystery as ever.

A less scientific theory has been offered in this particular instance. It is suggested, as the conjurer had threatened his wife to “trouble” her on the return of the day of his decease, or burial, that possibly his conjuring crew – for it is assumed that he was in league with others – might for the credit of magic in general, and their late confederate in particular, have planned a scheme for fulfilling his threat. But this supposition leaves the mystery as great as ever; for if the movements of the pans and chattels were effected by mechanical means, no uncommon sight and shrewdness could be needed to discover them. It is said that professional jugglers do more wonderful tricks. Perhaps so. But who was the juggler here? Where was he concealed? And where was his apparatus? Where were the wires, and who were the wire-puller? A little stone-floored cottage can hardly be compared with a theatre expressly arranged with stage and machinery for organised and avowed deception.

[,,,]

From ‘A Mendip Valley’ (1892) by Theodore Compton.