Norfolk Mystery House.

“A genuine oil well.”

Government experts are confident, says a news agency, that there is a genuine oil well at Swanton Novers Rectory, and they state that the house must be pulled down because if it were bored from outside the spring might be missed. It cannot be said how long the oil will last when struck. The theory that the liquid evaporated and condensed on the ceiling is stated to be correct.

September 5th, 1919.

Hull Daily Mail.

the status of experts.

No trick at the oil rectory.

Mr Nevil Maskelyne, the famous conjuror, who has paid a visit to the rectory at Swanton Novers, Norfolk, to investigate the mystery of the dripping of oil, declares it is no hoax. “There is, ” he said, after inspecting the rectory and the samples of oil, “only one solution to the mystery. This house is built over an oil well. Everything points to that. The samples are crude paraffin of heavy density. The oil has vaporised and the vapour has ascended towards the ceiling. Striking the changed antmospheric condition, it has condensed and rained down in liquid form. You can see by the dry state of the laths and plaster that it does not leak through the ceiling. It creeps up as vapour and comes down as liquid. None of the samples is of manufactured oil. The point is that the whole building is saturated with oil. To ascertain precisely how it reaches the points from which it gushes would probably involve pulling the building down.

In view of this statement the following, from another paper, is of special interest:- Government experts have solved the mystery of the “oily rectory” of Swanton Novers, Norfolk. The thoery which was hit on early in his harassing experience by the rector, the Rev. Hugh Guy, is correct – the house is built over, or around, a genuine oil well, and the experts are of opinion that the whole building – a double fronted Victorian villa in its own grounds – will have to be pulled down, because if the oil were bored for from the outside it might easily be missed. A corollary theory that the oil evaporated and condensed is supported by men of science. The experts advance no opinion with regard to the length of yield when the oil well is struck.

Liverpool Echo, 5th September 1919.

Weird Happening In Rectory

Floods of paraffin and petrol

Experts baffled

By a Special Commissioner.

Petrol, paraffin, methylated spirits, and water have invaded a Norfolk rectory, but their presence constitutes one of the greatest of modern mysteries. No one can discover whence they came, but there is not the slightest doubt as to their arrival, which has evicted the Rector and his wife from their home. Some fifty gallons of the liquid, which, with a hiss and a spurt, issues from the ceilings of different rooms have been collected, and at least one householder has found in it a source of free lighting.

The rectory where the extraordinary happening has occurred is a substantial house built in 1848, in the midst of an opulent agricultural population at Swanton Novers, Norfolk. I have visited the rectory there, tasted the falling oil, and interviewed various expert persons whose testimony is not to be lightly regarded.

Early last month there was observed in Norfolk an earth tremor, comparable to nothing so much as the vibrations felt there at the time of the great enemy offensive of March 21st, 1918. Whether this had anything to do with it is mere speculation, but shortly afterwards the Rector, the Rev. Hugh Guy, and his wife began to complain of a smell of paraffin. They took a fortnight’s holiday. On their return they found the nuisance ten times worse. Their furniture was saturated. They removed it to a garage, and they themselves sought temporary refuge in the house of a church warden.

About the fact that oil is dripping from the ceilings intermittently and collecting on the floors there is no room for doubt. A large firm of motor engineers inNorwich have had samples of it submitted to them. Some of it, they say, is paraffin, some of it they declare to be petrol, as good as any that they have to sell.

The problem is to find out where the oil originates, and what is the mode of its conduction. One hears a hissing, spurting noise, continues our correspondent. This occurs during the daytime only. You rush to the apartment indicated by the sound, and you find a pool of mingled oil and water on the floor, and a corresponding patch upon the ceiling, still exuding drops and bubbles.

On the occasion of my last visit, I met the local builder and several other experienced, practical people. They had explored the subject with the most patient detail. They could do nothing but afirm the facts observed and hazard theories which they themselves at once rejected.

Mrs Gray pointed out to me a row of bottles on the drawing-room mantelpiece all containing samples of mingled water and oil – paraffin, petrol, and methylated spirit. “This, ” she said, “has all been collected from the drip of the ceilings, or scooped up from a hole caused by removing a brick from a saturated floor. The curious thing is that the cascade only takes place in the daytime, and seldom or never during the night. I am unaware that oil has ever fallen between ten o’clock at night and eight in the morning. The inference would seem to be that the fall has something to do with the vibration caused by people moving about.”

But I put it to Mrs Gray that the fall had gone on in much the same degree during the time that the family was holiday-making and the house was unoccupied. She admitted that it was so.

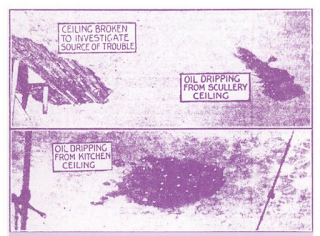

From whatever theoretical point of view you approach the problem, you come up against a dead wall of unlikelihood. I have had a interview with one of the official architects of the norwich Diocese, whose lifetime has been spent in looking after the fabrics of churches and parsonages. “I have been spending hours to-day at Swanton Novers,” he said. “While I was talking things over with Mr Grey, we heard a hissing sound in the kitchen. We rushed thither, and found that more oil, petrol apparently, had fallen. It lay in a pool on the floor. The ceiling above was wet with it. I pulled down the lath and plaster of the ceiling and took up the floor boards of the room above. There was dryness everywhere, and no sign of a channel or conducting medium by which the liquid could have travelled. The case is inexplicable to me. In fact, it is uncanny.”

Dundee People’s Journal, 6th September 1919.

Ceilings Drip 50 Gallons of Oil.

… Experts from the Lynn oilfields have visited the rectory and made an examination of samples, but no declaration was made. Their only opinion was given to a policeman on duty : “It is very interesting.” The hole in the kitchen is now three feet deep and is still saturated with paraffin. The water came from the ceiling down the stairs into the kitchen.

…

Evesham Standard and West Midland Observer, 6th September 1919.

The History of a “Short” Story.

Now that the “ghost” of the rectory at Swanton Novers has been laid, it may be of interest to know how the story first obtained publicity. The first intimation of the phenomenon reached a News Agency one morning from a local individual who was not its regular correspondent. The sub-editor at first threw down the item as one of no general interest, but later in the day included it in the agency’s news service merely to fill up a gap in a rather slack day. The London Evening Press ridiculed the item, but a morning paper seized it next day as a good “silly season” topic. London journalism then jumped at it unanimously, and since then hundreds of columns by experts and special correspondents have appeared regarding it. Had the original item not appeared, the world would probably have missed the intensely interesting speculation which the “ghost” has aroused. It is interesting to note that one London evening paper, which bluntly characterised the original paragraph as a “fake,” on Tuesday night devoted two columns of very serious writing as a final contribution to the solution of the mystery.

Thursday 11th September 1919.

Leicester Evening Post.

The Oily Rectory.

The Rev. Hugh Guy, of the “oily” rectory at Swanton Novers, Norfolk, was asked in a telegram to say whether there have been any more drippings since the girl was accused. The rector’s telegraphic reply was:- “No more drippings whatever. – Rector, Swanton Novers.”

Western Mail, 13th September 1919.

Maskelyne was born in 1863 to stage magician John Nevil Maskelyne. Following his father’s death he assumed control of Maskelyne’s Ltd.[1]

In wireless telegraphy he was the manager of Anglo-American Telegraph Company which controlled the Valdemar Poulsen patents.[2]

He was a public detractor of Guglielmo Marconi in the early days of radio (wireless). In 1903 he hacked into Marconi’s demonstration of wireless telegraphy, and broadcast his own message, hoping to make Marconi’s claims of “secure and private communication” appear foolish.[3][4][5]

He married Ada Mary Ardley (1863–1901) about 1890 in England, United Kingdom. They had three sons, John Nevil Maskelyne, who was to become a noted author on railway matters in the early 20th century, Noel Maskelyne and Jasper Maskelyne, who continued the family tradition of professional magic.

He died in 1924.

Wikipedia

Professor A. V. Williams Jackson of Columbia University wrote in his work From Constantinople to the Home of Omar Khayyam (1911):

Baku is a city founded upon oil, for to its inexhaustible founts of naphtha it owes its very existence, its maintenance, its prosperity… At present Baku produces one-fifth of the oil that is used in the world, and the immense output in crude petroleum from this single city far surpasses that in any other district where oil is found. Verily, the words of the Scriptures find illustration here: ‘the rock poured me out rivers of oil.

Oil is in the air one breathes, in one’s nostrils, in one’s eyes, in the water of the morning bath (though not in the drinking water, for that is brought in bottles from distant mineral springs), in one’s starched linen – everywhere. This is the impression one carries away from Baku, and it is certainly true in the environs.[24]

By the beginning of the 20th century, half of the oil sold in international markets was being extracted in Baku.[25] The oil boom contributed to the massive growth of Baku. Between 1856 and 1910 Baku’s population grew at a faster rate than that of London, Paris or New York.4

Wikipedia

Oswald Williams (1880-1934) travelled and performed throughout America and Europe from 1907 until the outbreak of Word War 1 with an illusion show which had about one ton of equipment, three male assistants and one female.

Biography

Designed and built his own illusions such as The Merry Widow Hat, The Vanishing Lady, Noah’s Ark, The Box of Tricks, The Homing Bells (used by David Devant at the First Grand Seance of the Magic Circle) and The Dizzy Limit to name but a few.

Also noted for smaller effects such as the Torn and Restored Strip of Paper.

Oswald Williams billed himself as “England’s Foremost Illusionist”. He performed the following stage act in London during 1918: The Vanishing Bowl of Water, the homing Bells, lady of the Bath Novelty, Torn and restored Paper Strips, and ended with the Diamond Girl. [1][2]

His 1931 performance at Maskelynes in London was described in Holden’s Programmes of Famous Magicians which states he was assisted by Miss Mary Maskelyne. The act included the Square Pig Novelty (U. F. Grant’s); “Seeing is Believing”; Topsy Turvy Bottle; Rings to Chain; Bill in the Cigarette; “Once Upon a Time”; “Invisible Wine”; Ark Illusion; “Grandmother’s Work Basket”; and “The Dizzy Limit Illusion”.

Note: Oswald Williams wrote a letter to the Conjurers’ Monthly Magazine (Oct 30, 1906) explaining, “I am not Oswald Williams of Cardiff. This gentleman’s name is Charles Oswald Williams; he is a very clever amateur conjurer, but I believe has never been on the Music Halls.I met him some years back and we were so struck at the strange coincidence in the similarity of our names and craft that we were photographed together.”

Wikipedia